In the past two months I’ve attended two lectures on the topic of human remains in museum collections. The talks were part of a University of Michigan lecture series titled It’s Alive! Rediscovering Institutions of Living Collections. I found the questions generated by these talks to be phenomenally interesting, particularly those concerning how to balance the ethical curation of human remains with the tendency of museum-goers to lavish them with morbid, fetishizing attention.

It was very difficult to find a public photo of the Institut, so here is a festive photograph of the Christmas market in Stuttgart, instead.

The first talk, titled Policy and Practice in the Treatment of Human Remains in German Museum Collections was given by Robert Jütte, director of the Institute for the History of Medicine in Stuttgart. [Sidebar: While Jütte’s English was flawless, over the course of the lecture he kept saying “skeleton in the cupboard”, which I found charmingly German of him]. His talk covered the loaded history of the curation of human remains in Germany, ranging from the atrocities of the Nazi regime to the cover-ups of the German Democratic Republic . There are some striking parallels between the U.S. and Germany – just as our history of the attempted genocide of indigenous peoples has generated NAGPRA legislation, the prevalence of Nazi war dead in museum collections during the 20th century posed a series of legal and administrative dilemmas that German museums were forced to confront. Between 2000 and 2003 a private committee (the Stuttgart Working Group on Human Remains in Collections) was established to set up a series of guidelines to try and resolve such issues. This set of recommendations became a document that I think all bioarchaeologists should have in their archives, the Deutscher Museumsbund’s set of Recommendations for the Care of Human Remains. I’m linking to the English translation of the document and attaching a pdf at the end of the post. The Recommendations cover issues of identification, curation and reclamation, and provide an excellent compass with which to navigate challenging issues of museum curation.

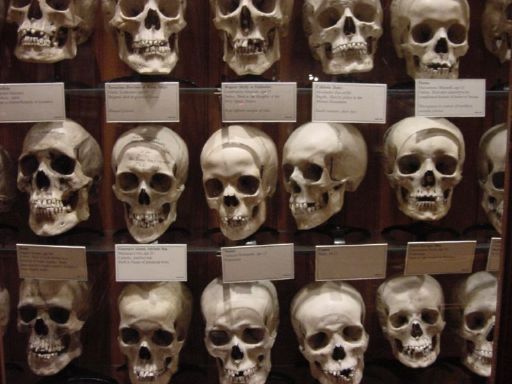

The second talk, titled Exquisite Corpses: Our Dialogue with the Dead in Museums, was given by Dr. Robert Hicks, director of the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia (I know, I know, it’s like the organizers of the lecture series were obsessed with umlauts). His talk was far more eclectic than Jüttes. Instead of addressing a central theme, Hicks introduced a plethora of different case studies involving the sometimes controversial subjection of human bodies to the ‘post-mortem gaze’, from the meretricious trafficking of human remains as relics in Pakistan, to the anatomical wax ‘venuses’ from the Museo La Specola in Florence. Over the course of the talk, the audience was bombarded with imagery. The wax head of Madame Dimanche. The Hyrtl skulls. Holbein’s Dance of the Dead. The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp. Medical plates illustrating piebald albinism. Alice Cooper album covers. The Quay Brothers’ Through the Weeping Glass. Cupid and Centaur in the Museum of Love. By the end of the lecture I was overwhelmed, but my near-indecipherable scribbles indicate that the take home point was that museums should “promote a new discourse about post-mortem imagery, offer inventive associations and contexts, invite a new or rediscovered aesthetic” and “be brokers of cultural perspectives”. Which sounds about as clear and easy to implement as any of the vague statistical techniques I describe in all of my conference abstract submissions….

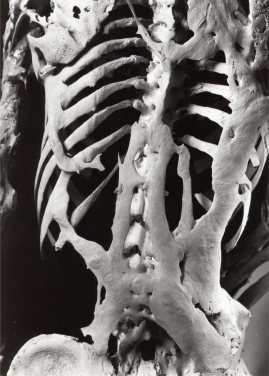

Despite their disparate approaches to the topic, both Jütte and Hicks converged on one point – they both expressed a distaste for Gunther von Hagen’s Body Worlds exhibition. Jütte underscored the controversy that has followed the exhibit since its initiation (and inadvertently came up with an excellent pun, when he described a situation in which von Hagen was planning to position the plastinated cadavers as having sex “bawdy”). Hicks did not go into much detail, and merely mentioned that he did not care for von Hagen’s work, noting that many of the representations of human movement in the exhibit were anatomically inaccurate.

I found their aversion to these types of displays intriguing. It would appear that von Hagen is to anatomists as Jared Diamond is to anthropologists. Both directors’ attitudes suggested that the Body World’s exhibition was somehow more crass than any of the anatomical exhibits housed in more upstanding venues like museums or universities. In part, their response may be the result of Body World’s overtly commercial nature, or it may be related to the ethical controversy generated by von Hagen’s approach to obtaining specimens. However, museums are not immune to such problems themselves. Jütte tenderly described one of the most famous anatomical specimens in Germany, the sagitally cross-sectioned body of a woman who drowned herself in the late 19th century after discovering she was pregnant. The “Marburger Lenchen” is one of the most popular exhibits in the Medical History Museum in Marburg. The specimen was obtained at a time before informed consent was required for donations, so ethically speaking, her display should be anonymous. Unfortunately, the woman’s name is still associated with the exhibit, and the museum cannot raise the funds necessary to provide a display that outlines the ethical nuances of the issue. Importantly, Jütte never suggested that the museum remove the specimen from display until the issue was resolved.

Similarly, Hicks provided an animated description of the Mütter Museum’s soap lady, a corpse that underwent a unique taphonomic process involving the conversion of soft tissue into adipocere. He proudly highlighted the Soap Lady’s “celebrity status”, noting that she was frequently used as a test subject by members of the International Mummification Conference. She is such a popular attraction that her likeness has even been made into an actual bar of soap, that you can purchase in the Mütter Museum gift shop. Hicks distributed one of these as an audience prize after the end of his talk. But, as in the case of the Marburger Lenchen, the “Soap Lady” did not donate her body to science, nor did she ever give her consent that her corpse be publicly displayed in a museum. As Hicks freely admitted, the corpse was donated to the museum under highly questionable circumstances, and records indicate that early anatomist Dr. Joseph Leidy obtained the remains after they were exhumed by “pretending to be the corpse’s grandson” .

I’m using these examples to illustrate what I see as a double-standard when it comes to the public display of human remains. Consent and accuracy have been used to undermine the ethics underlying the Body Worlds exhibits, but there are just as many ethical issues surrounding the display of historical human remains in museum collections. I’m not necessarily standing up for von Hagen, as heaven knows he’s a controversial enough character. I’m also not suggesting that we remove all human remains from public display – I’m bioarchaeologist for a reason, and I find bones both scientifically and aesthetically appealing. I do, however, find it hypocritical to assert that displaying human remains for profit and publicity is only acceptable in museum contexts. The morbidly curious will attend exhibitions of human remains no matter what the forum, and there’s no guarantee that they will be more respectful or understanding of the dead simply because there is an explanatory plaque present. The question that I wanted to ask both speakers after their talks was what differentiated their public from von Hagen’s, because I have a sneaking suspicion that the answer is “nothing”.

Museums and exhibitions like von Hagen’s both benefit from the public’s perverse fascination with human remains, and this is simultaneously a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, it generates interest in science and anatomy, while on the other, it often attracts an uncomfortable public gaze that treats remains as fetish objects, rather than historical and medical artifacts. This isn’t a problem that can be solved by simply writing off commercial exhibitions as crude, low-brow entertainment while glorifying the unsullied and blameless institution of the museum. Navigating the situations in which it is appropriate to display human remains necessitates a nuanced approach to issues of provenience, consent and audience, no matter what the context. Which, in the end, is why I found both speakers so stimulating, despite being dissatisfied with their conclusions. Even though we don’t have all the answers yet, at least someone has started the dialogue.

On that note, how do you feel about the public display of human remains? What do you consider appropriate or inappropriate contexts for such display? What is your reaction towards the situations outlined above?

Pdf version: Deutscher Museums Bund 2013 – Recommendations for the Care of Human Remains in Museums and Collections

Image Credits: First Photo of Mütter skulls found here. Photo of Weinachtsmarkt in Stuttgart found here. Skeleton with evidence of FOP from here. Image of soap lady soap from the Mütter Museum website. Screenshot of Body Worlds Exhibit flyers taken from Body Worlds Website.

Reblogged this on Beauty in the Bones.

LikeLike

I too see the double standard that you describe between “righteous” museums and “sleazy” traveling shows. At Hopewell Culture National Historical Park where I volunteer, there used to be an exhibit inside Mound City (from about the 60s until NAGPRA) of a bisected mound showing the layers of earth with the human skeletal remains of the person who had been buried there on display through the glass, covered in sheets of Mica. In a small town like Chillicothe OH, where people tend to not migrate, there were visitors even last summer (20 years since the display was removed) who would describe how memorable that exhibit was when they saw it when they were schoolkids 40 years ago. It’s probably one of the most frequently mentioned topics of older locals to the visitor center (“whatever happened to that one mound…”).

The dilemma you describe of wanting visitors to engage with the past while staying in the realm of the respectful is really relevant. I don’t know what the right answer is either. I think that working with descendants is the best option we have though.

Excellent post, keep up the good work!

LikeLike

Jocelyn,

Thanks for the thoughtful comment! I think this is a particularly loaded dilemma in the U.S., largely as a result of NAGPRA legislation. That said, while NAGPRA has done a lot to increase our awareness of the culturally sensitive nature of human remains, there’s clearly still a lot of room for discussion, particularly when it comes to remains that were collected before consent was a necessary step in the curation process…

– JB

LikeLike

I think this is a very relevant issue and one that is not getting as much discussion as it deserves. When I started my masters work I was working with bioethicists who were amazed there was no overarching ‘code of ethics’ for bioarchaeologists concerning the treatment of human remains. It really inspired my work (re: commodification of cadavers for biomedical use) and has challenged much of what I was taught in the classroom. What is considered respectful treatment of the dead varies from scientist to scientist and from scientist to living descendant. I hope to see more of this kind of work in the future. Thanks for putting this out there.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Bodies and academia.

LikeLike

Pingback: Lots ‘o’ Links: Finals Edition November 23 – December 13 2013 | Scientia and Veritas

Pingback: Blogging Archaeology: January | Bone Broke

Pingback: Body Worlds Vital Exhibition Comes To Life | These Bones Of Mine

Thanks for the great read! I’m also very interested in what makes some human remains acceptable to display, especially when consent cannot be given. It seems that North Americans and some Europeans have been sensitized to the issue by repatriation movements, but there is no real consensus about what is acceptable when it comes to displaying non-Indigenous human remains. I’m planning to contribute to this area with my PhD research and hope there are more conferences like this one in future – I was clearly a few years late to the party for this one!

LikeLike