Perhaps the Gibraltar child’s wistful expression simply reveals a heartfelt longing for pizza

Richard Wrangham recently came and gave a talk as part of a four-field Anthropology colloquium here at Michigan. He presented an idea that’s been gaining ground in biological anthropology in recent years – namely, that humans are adapted to consume a diet of cooked food. Having eaten my fair share of pizza recently (dissertation proposal + grading = questionable nutritional decisions) I was inclined to agree with him. However, he didn’t just appeal to the audience’s craving for junk food. In fact, Wrangham’s approach was particularly apropos for a four-field audience, as he focused on several different lines of evidence to make his argument:

ETHNOGRAPHY: Wrangham underscored that cooking is essentially a universal undertaking among human hunter-gathers. Broad scale surveys suggest that across cultures, the evening meal is cooked, while the raw food component of the diet consists primarily of snacks that are eaten out of camp.

If you Google Image search “hunters cooking”, this is what you get.

ANATOMY: Humans’ relatively small guts and laughably puny molars suggest a suite of irreversible changes to the physiological mechanisms that most mammals use to digest their food. Such changes would likely only be possible if early members of our genus were relying on something besides their bodies to process what they ate. Similarly, Wrangham pointed to the ‘obligate territoriality’ of early members of the genus Homo as evidence that the control of fire likely arose early on in the course of human evolution. As he wryly noted, he wouldn’t be “game” for sleeping on the Serengeti today without a fire…Get it? Game? Like meat? (Editor’s Note: Wrangham did not actually make that pun – that’s all JB).

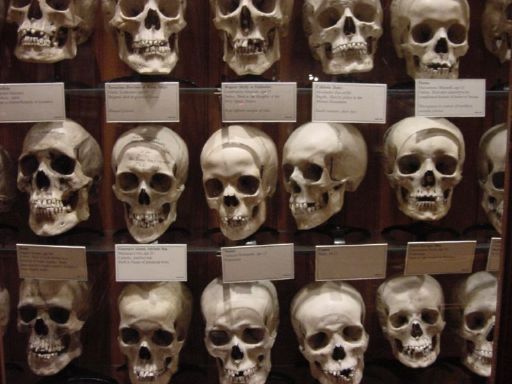

Molar size of humans relative to those of a robust autstralopithecine. Pretty pathetic, huh?

PALEOANTHROPOLOGY: Recent research (Henry et al., 2011) has investigated the contents of Neanderthal dental calculus, a fairly disgusting hard plaque that generally forms around the cementoenamel junction of teeth. While Neanderthals have previously been argued to have been overwhelmingly dependent on meat, exploring the contents of their calculus revealed that not only did Neanderthals eat plant foods, they ate cooked plant foods. Some of the phytoliths and grains found ‘caked’ onto Neanderthal teeth showed damage that is characteristically caused by cooking, suggesting that this practice dates back to at least 50,000 years BP.

REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH: Here, Wrangam emphasized the results of a study of raw foodists that was conducted by German researchers in the 1990s (see Koebnik et al., 1999). Their research demonstrated a strong positive correlation between the % raw food component of the subjects’ diets and the % of the study population that was amenorrheic. These results suggest that most women living on a very high-quality raw food diet, incorporating meat, non-seasonal produce and oil, still cannot reproduce. In sum, if you want to increase your fitness, make sure to eat some pizza every once and awhile. At least, that’s how I interpreted it.

Bonobo eating a marshmallow. I swear I’m not making this stuff up. It’s from the Daily Mail, so it must be credible…

ANIMAL BEHAVIOR: As anyone who has ever kept a pet will know, domesticates prefer to pilfer your food rather than eat the dry and oddly-colored pellets that fill their bowls. Wrangham underscored that most animals prefer cooked food when given the option. This has been demonstrated by food preference tests in captive apes, and there’s at least some evidence that wild chimpanzees will seek out indigenous plants that have been roasted in bushfires.

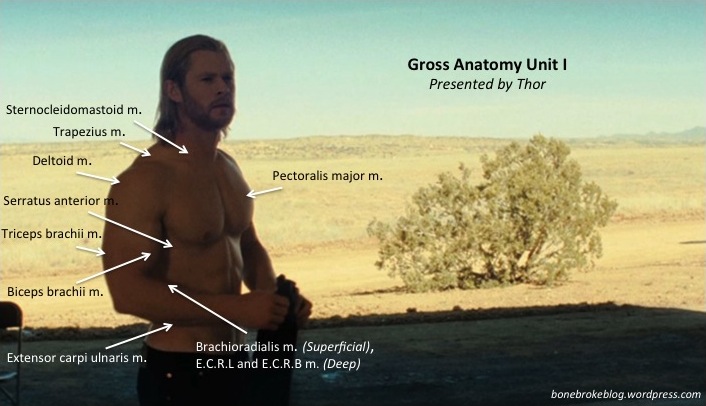

Maintain your body mass, little buddy!

PHYSIOLOGY: A preference for cooked food makes sense, because cooking food increases its net energy benefit to most animals. Wrangham and his student Rachel Carmody have conducted a number of intriguing studies investigating the effects of differentially processed food on the health of lab populations of Mus musculus, or house mice. They found that diets of both cooked or cooked and pounded food allowed mice to maintain their body mass, while diets of raw food led to a significant drop in weight over the course of several weeks. Similarly, studies of both human ileostomy patients and captive Burmese pythons suggest that the key benefit to cooked food is not necessarily increasing the caloric content of the food itself, but rather lies in its ability to reduce the costs of digestion associated with food processing. In fact, the python study demonstrated that consumption of cooked food, rather than raw food, reduced the costs of digestion by 12.5%.

Personally I think I would rather work with mice, but to each their own…

The lecture was certainly fascinating. I think that Wrangham presents a compelling hypothesis, and he creatively incorporates a number of different lines of evidence to strengthen his arguments. Unfortunately, as with most behavioral aspects of the deep palaeoanthropological past, it’s not directly testable – at least not right now. However, more studies of ancient dental calculus, particularly if combined with more evidence on contemporary reproductive constraints along the lines of Koebnick et al.’s study, have the potential to shed even more light on the relationship between cooking and the evolution of our genus.

References:

Boback SM, Cox CL, Ott BD, Carmody R, Wrangham RW, & Secor SM (2007). Cooking and grinding reduces the cost of meat digestion. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Part A, Molecular & integrative physiology, 148 (3), 651-6 PMID: 17827047

Boback SM, Cox CL, Ott BD, Carmody R, Wrangham RW, & Secor SM (2007). Cooking and grinding reduces the cost of meat digestion. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Part A, Molecular & integrative physiology, 148 (3), 651-6 PMID: 17827047

Carmody RN, & Wrangham RW (2009). The energetic significance of cooking. Journal of human evolution, 57 (4), 379-91 PMID: 19732938

Carmody RN, & Wrangham RW (2009). The energetic significance of cooking. Journal of human evolution, 57 (4), 379-91 PMID: 19732938

Henry AG, Brooks AS, & Piperno DR (2011). Microfossils in calculus demonstrate consumption of plants and cooked foods in Neanderthal diets (Shanidar III, Iraq; Spy I and II, Belgium). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108 (2), 486-91 PMID: 21187393

Henry AG, Brooks AS, & Piperno DR (2011). Microfossils in calculus demonstrate consumption of plants and cooked foods in Neanderthal diets (Shanidar III, Iraq; Spy I and II, Belgium). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108 (2), 486-91 PMID: 21187393

Koebnick, C., Strassner, C., Hoffman, I., & Leitzmann, C. (1999). Consequences of a longterm raw food diet on body weight and menstruation: results of a questionnaire survey. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 43, 69-79

Koebnick, C., Strassner, C., Hoffman, I., & Leitzmann, C. (1999). Consequences of a longterm raw food diet on body weight and menstruation: results of a questionnaire survey. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 43, 69-79

Wobber V, Hare B, & Wrangham R (2008). Great apes prefer cooked food. Journal of human evolution, 55 (2), 340-8 PMID: 18486186

Wobber V, Hare B, & Wrangham R (2008). Great apes prefer cooked food. Journal of human evolution, 55 (2), 340-8 PMID: 18486186

Wrangham R, & Conklin-Brittain N (2003). ‘Cooking as a biological trait’. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Part A, Molecular & integrative physiology, 136 (1), 35-46 PMID: 14527628

Wrangham R, & Conklin-Brittain N (2003). ‘Cooking as a biological trait’. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Part A, Molecular & integrative physiology, 136 (1), 35-46 PMID: 14527628

Image Credits: Image of Devil’s Tower Neanderthal found here. Slice of pizza is a stock photo. Hunters cooking was, as mentioned, courtesy of a Google Image search. Robus and human dentition from anthropology.net. Bonobo cooking a marshmallow featured in the Daily Mail’s article on Kanzi, which, much like this post, is filled with dreadful puns. Mouse eating a cookie from this site. Image of python found here.

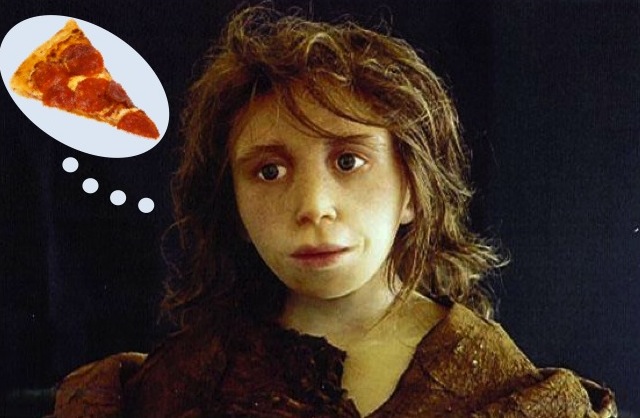

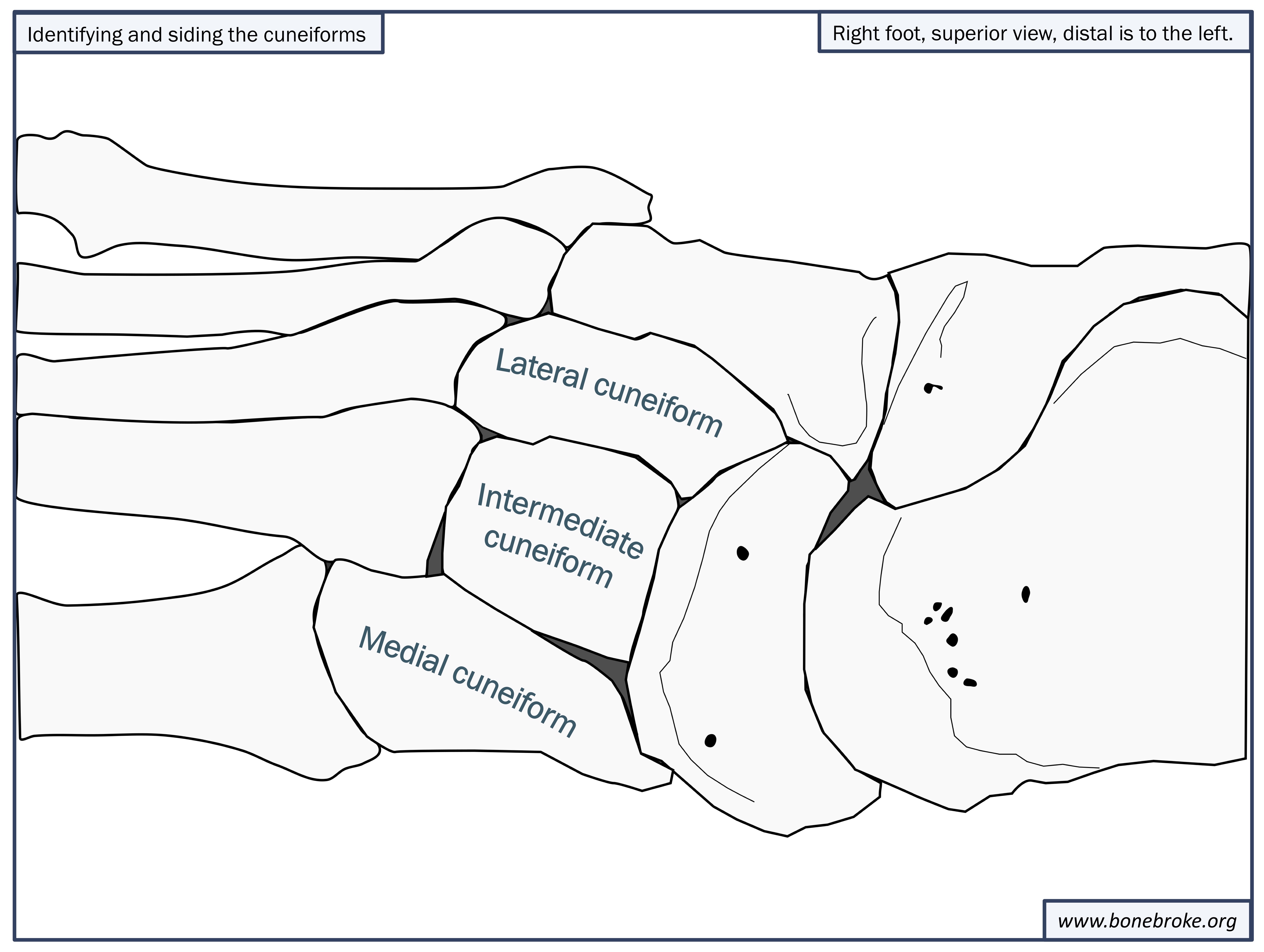

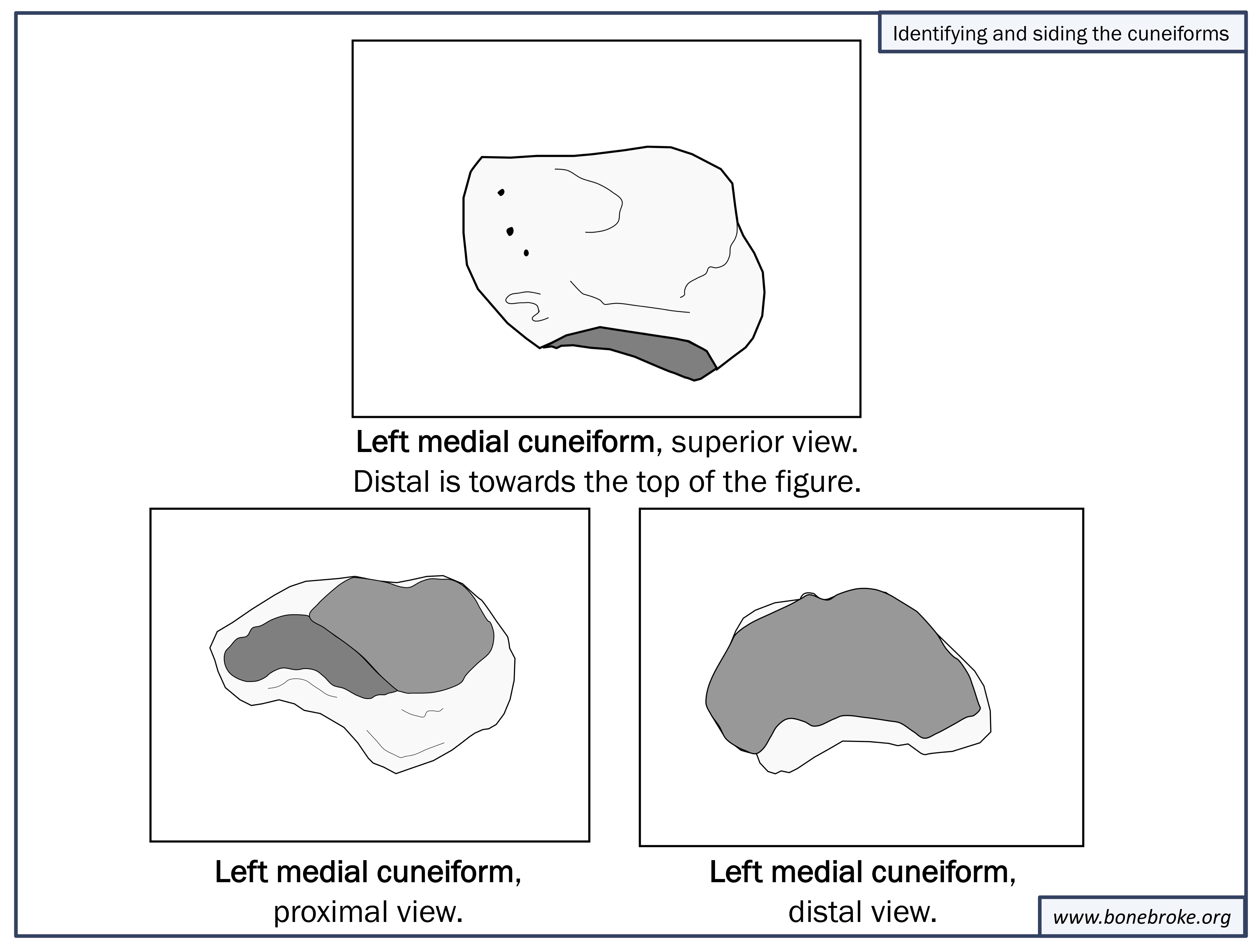

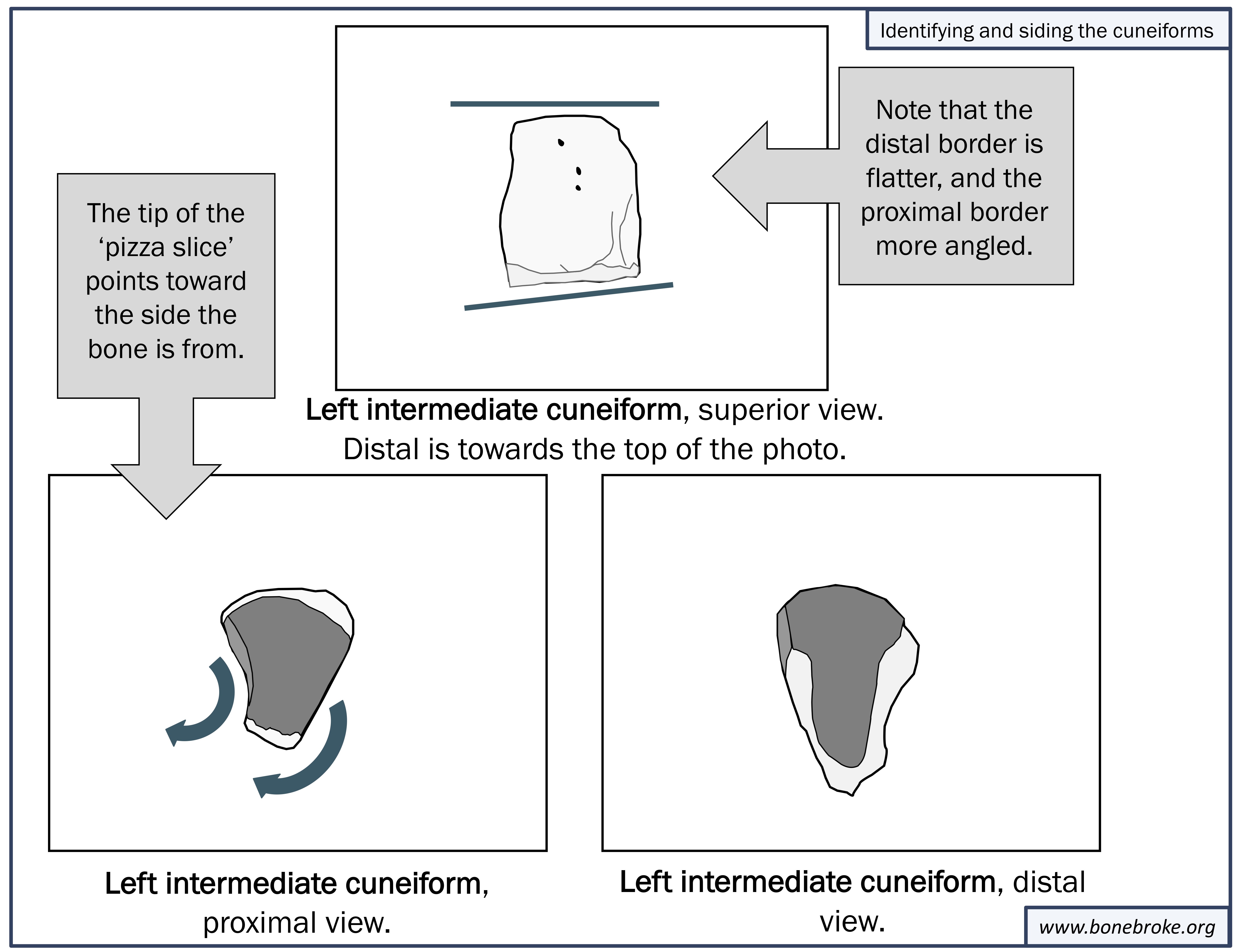

II. The Intermediate Cuneiform

II. The Intermediate Cuneiform

III. The Lateral Cuneiform

III. The Lateral Cuneiform