“It’s called Huerta del Manco,” she said in Spanish. “You know what that means?” “Huerta, si.” I told her. I’d come across the word before while translating archaeological texts and it was always used to describe orchards, groves or other types of cultivated land. “But… manco? No.” Rocío nodded, knowing it was time to resort to gestures “A manco is a person that has suffered from this”. She made a chopping motion over her left wrist.

I thought for a minute, melding the translations together in my head. “Orchard of the Amputees?” She grinned and started laughing as she could tell by my face that I’d figured it out.

Huerta del Manco is not the only unusual toponym in this part of Spain. My friend hails from the northeastern corner of Andalucía, a region famous for its exquisite mountain landscapes, which are protected in 2100 square kilometers of natural parks. These reserves are divided into three separate regions: Sierra de Cazorla, Sierra de Segura, and las Villas. In addition to “Orchard of the Amputees”, La Segura boasts such toponymic gems as Poyo Catalan (Catalonian Seat), Las Quebradas (The Broken Ones), and Santiago de la Espada (Santiago of the Sword).

We caught a large ALSA bus at the station in Jaén, spending three hours weaving through Jiennense campiña, the endless, rolling hills of olive groves so characteristic of the southern frontier of the province. Released from the museum, I was content to simply sit and gaze out the window, taking in the undulating terrain that rushed past us. I grew increasingly more excited as the occasional stand of pines broke the arboreal monotony of the continuous squat silver olive groves. I explained this to Rocío and she shook her head firmly, indicating that the campiña was all very well and good, but not really worthy of aesthetic note. “Wait until we catch the next bus” she told me, “wait for the mountains”. After three hours we reached the town of Puerte de Genave, where we boarded a smaller bus with a capacity of only sixteen people. The bus-driver gave me a curious look while we were loading up. “You going to Espada?” she asked skeptically, before Rocío jumped in assured her that yes, the strange, pale foreigner was already being supervised.

We caught a large ALSA bus at the station in Jaén, spending three hours weaving through Jiennense campiña, the endless, rolling hills of olive groves so characteristic of the southern frontier of the province. Released from the museum, I was content to simply sit and gaze out the window, taking in the undulating terrain that rushed past us. I grew increasingly more excited as the occasional stand of pines broke the arboreal monotony of the continuous squat silver olive groves. I explained this to Rocío and she shook her head firmly, indicating that the campiña was all very well and good, but not really worthy of aesthetic note. “Wait until we catch the next bus” she told me, “wait for the mountains”. After three hours we reached the town of Puerte de Genave, where we boarded a smaller bus with a capacity of only sixteen people. The bus-driver gave me a curious look while we were loading up. “You going to Espada?” she asked skeptically, before Rocío jumped in assured her that yes, the strange, pale foreigner was already being supervised.

What with luggage, passengers, and a large cardboard box that appeared to contain an anvil based on the effort required to move it, it was a already a full ride. However, within minutes of getting on the road the small vehicle stopped once more, to admit a grandmother, mother and granddaughter onto a bus with no remaining seats. This proved no deterrent – the trio of fashionably dressed teenage girls behind us squished together in a single row, and the young girl perched on her grandmother’s lap, everyone laughing and grinning at the jostling, uncomfortable ride that would have been considered an inconvenience anywhere else. This was clearly an area where everyone knew each other well. We wound through a narrow road that passed through the steep, stepped town of La Puerta de Segura before passing into a more open plain that revealed broader glimpses of the local topography. I craned my neck, ducking and weaving to catch a glimpse of the view as we flashed past a small be-castled town, La Segura de la Sierra, perched on a distant high peak. The mountains were towering and sparsely forested, vast inclines that sprung up impassively a few kilometers away from the road. As we continued deeper into La Segura the road became more tortuous, and the broad expanse of the deep blue reservoir El Tranco hove into view as we motored steadily upward.

Rounding a bend, the vehicle startled three small mountain goats (likely representatives of Capra pyrenaica, the Spanish Ibex), who bounded down the steep slope into the forest. Every ten minutes the bus stopped at another little hamlet to unload more old women laden with shopping bags, all of them talking continuously. Within an hour, and after a brief spate of negotiation with the bus driver, Rocío and I were dropped off at a local crossing called Cruz de la Revuelta, and her parents drove down in their white four-wheel drive to collect us. I peered eagerly out the window as dusk settled over the fields. We had arrived in Huerta del Manco just as the local shepherds were taking in their flocks for the night, and the car crept past a vast number of the braying creatures, every one in ten bedecked with a large metal bell on a leather collar. A large mixed-breed dog jauntily trotted down the road after them, ears pricked up and tail held high.

Dinner consisted of a tortilla Española that Rocío’s mother Pepa deftly slid out of a cast iron pan and quartered, plus the typical array of simple yet staggeringly delicious Spanish fare: jamón Serrano, lomo, local bread, and sheep’s cheese. Pepa had also made small ceramic pots of arroz con leche for dessert, a sweetened rice pudding made with sugar and lemon, topped with a dash of cinnamon. While helping to clear the dishes, I realized that the family had an entire hock of jamón Serrano elevated on a stand on one kitchen counter. I was entranced. “What is that called?” I asked Rocio, pointing at the massive slab of meat. “Una jamonera” she told me simply, as if it were an apparatus as mundane as a coffee-maker or toaster.

Dinner consisted of a tortilla Española that Rocío’s mother Pepa deftly slid out of a cast iron pan and quartered, plus the typical array of simple yet staggeringly delicious Spanish fare: jamón Serrano, lomo, local bread, and sheep’s cheese. Pepa had also made small ceramic pots of arroz con leche for dessert, a sweetened rice pudding made with sugar and lemon, topped with a dash of cinnamon. While helping to clear the dishes, I realized that the family had an entire hock of jamón Serrano elevated on a stand on one kitchen counter. I was entranced. “What is that called?” I asked Rocio, pointing at the massive slab of meat. “Una jamonera” she told me simply, as if it were an apparatus as mundane as a coffee-maker or toaster.

Mountain nights provided a welcome contrast to the bustling and oppressive heat of late summer evenings in Jaén. The air was tinged with a slight chill that hinted at the gradual encroach of autumn, and the alpine silence was deep and near total, only occasionally punctuated by the cascading barks of local dogs. I woke the next morning after a death-like slumber, stumbling downstairs to find a massive pot of chocolate steaming on the gas stove. Rocío and I breakfasted on what she facetiously termed “churros de pan”, dipping thin slices of bread into glasses of the heated mixture of milk and melted chocolate. Her uncle joined us for breakfast, eating in a fashion that I came to realize was typical of the inhabitants of these mountain villages, eschewing the use of a fork and relying instead on a small, sharp knife called a navaja as his sole form of cutlery. He deftly carved off of hunks of bread, pieces of sheep’s cheese and bites of salchichón, cupping the food in one hand, with his thumb braced to act as a bulwark against the swift progress of the blade.

Mountain nights provided a welcome contrast to the bustling and oppressive heat of late summer evenings in Jaén. The air was tinged with a slight chill that hinted at the gradual encroach of autumn, and the alpine silence was deep and near total, only occasionally punctuated by the cascading barks of local dogs. I woke the next morning after a death-like slumber, stumbling downstairs to find a massive pot of chocolate steaming on the gas stove. Rocío and I breakfasted on what she facetiously termed “churros de pan”, dipping thin slices of bread into glasses of the heated mixture of milk and melted chocolate. Her uncle joined us for breakfast, eating in a fashion that I came to realize was typical of the inhabitants of these mountain villages, eschewing the use of a fork and relying instead on a small, sharp knife called a navaja as his sole form of cutlery. He deftly carved off of hunks of bread, pieces of sheep’s cheese and bites of salchichón, cupping the food in one hand, with his thumb braced to act as a bulwark against the swift progress of the blade.

We set off soon after to explore the village and its environs. In sharp contrast to my own far-flung upbringing, all of Rocío’s family history is nestled in one small valley in this mountain chain. Her father grew up in a village called Los Ruices, a stone’s throw to the northeast of Huerta, while her mother hails from the slightly larger town of La Matea, only a few kilometers southwest. Rocío showed me the fountain just beneath her house, explaining that most people in this part of the world still get their water from mountain springs since it tastes better than water from the tap. We visited her parents’ huerto, a large field a short distance from their house, where they grow potatoes, beans and peas, as well as tomatoes and cucumbers in their invernadero, or greenhouse. The northwest corner of the plot is marked by a flourishing pear tree; somewhat unwisely I told Pepa that the one pear that I had pilfered from it was delicious, and almost immediately received several pounds of pears in a large plastic bag to take back to the city with me.

After our brief and desultory perambulations we returned to the house for lunch, which in this part of the world is traditionally the largest meal of the day. Pepa had outdone herself, roasting chicken and potatoes in a broth of “garlic, lots of onions, and a little olive oil”. The potatoes turned the bright, buttery yellow that signals roasted perfection, and I mused, as I have many times since my arrival in Spain, that they know how to cook potatoes in this country, a feat that has yet to be accomplished in my homeland. The next afternoon Pepa prepared migas, a sort of deconstructed dumpling made by pan-cooking a mixture of flour, water, shredded potato and salt, one that can be topped with everything from roasted pepper to cured meat. Watching me gleefully spear several links of chorizo to adorn my migas, Pepa gestured at them with her hand. “Those were made here,” she said off-handedly. After further questioning it came out that not only does Rocío’s family cure their own jamón Serrano, but they have also always prepared their own spiced sausages. “I bought some from the store once” Pepa told me, by way of explanation. “They were not very good. ”

Over the next two days we passed all of our time either sleeping, walking or eating. The local roads wound up and down hillocks, linking chains of tiny mountain villages that sometimes contained as few as four houses. The sun coating the hills and peaks was warm but gentle, the brutal glare of Andalucían high summer having burned off several weeks before. As the afternoon progressed clouds rolled across the valley, momentarily plunging small peaks and valleys into shadow, and wafts of the sweet, viscerally rural scent of dried sheep dung provided a constant perfume. We trekked for several miles to visit a local waterfall and riverbed, both of which were dry after the pronounced aridity of the summer. Rocío joked that she was ushering me around a ghostly landscape, deeming the local site “la cascada fantasma”.

While exploring the caves around the waterfall I heard the hushed rustling of furtive animal movement in the tall grass, and glanced up to see a fox tail flicker across the opposing slope. This was still a region where animals outnumbered people – in addition to extensive gardens, the local populace tended herds of goats, cattle, and horses, most of which were guarded with by quiet professionalism by large mixed-breed dogs. Traversing the valley’s tranquil hills, ambling through quiet streets where old men sipped coffee and women collected laundry, I marveled at the remarkable preservation of the traditional country way of life in this part of Spain. It was as if the world had taken a deep breath in 1952 and forgotten to ever exhale; time, if not frozen, certainly seemed to proceed at a more languid pace in these mountains, effecting change as slowly as honey being poured over the hills. In America, these small rural communities are rapidly disappearing, a socioeconomic shift wrought by the government’s increasing support for large-scale commercial agriculture. On one of our strolls I asked Rocío if she ever planned to return to her town, a part of me fearing the inevitable negative response that characterizes so many young Americans’ reactions to their home soil. “Of course,” she assured me in Spanish “Es mi tierra” – “It’s my earth”.

My last morning in the village I trooped down the cement path to La Fuente del Sancho, to fill the dark blue plastic water jug used to replenish the household drinking supply. The squat yellow-capped bottle has a length of twine tied around its neck to make it easier to handle, and you must forcefully plunge the buoyant, empty base into the fountain pool to lower the vessel beneath the spigots. I was filling the last third of the jug when I heard a sudden rush of noise behind me. I felt a momentary panic and looked up, expecting to find a pack of feral dogs or irate locals defending their turf, until I realized it was just one of the town’s ubiquitous flocks of sheep. Bleating and rolling their eyes back, they crowded behind me in fearful surprise, slamming into one another in their haste to avoid the strange alien creature pirating their water supply.

Forearms dripping wet, I muscled the bottle out of the water and backed off as I screwed the cap on tightly, granting the rightful owners of the water supply access to their territory. As I headed back to the house, I realized that not even the sheep in this region made me feel unwelcome. I will always remember ambling through impressive peaks in the tranquil afternoon haze of late summer, fondly recollect the amazing hand-made delicacies unearthed from local larders and hear echoes of the jangle of bells announcing ovine movement several kilometers distant. However, what I know I will keep with me longer than any fleeting sensory memories of my trip is a deep and lasting appreciation for the incredible hospitality that I was shown by everyone I met on my visit to these timeless mountains.

Forearms dripping wet, I muscled the bottle out of the water and backed off as I screwed the cap on tightly, granting the rightful owners of the water supply access to their territory. As I headed back to the house, I realized that not even the sheep in this region made me feel unwelcome. I will always remember ambling through impressive peaks in the tranquil afternoon haze of late summer, fondly recollect the amazing hand-made delicacies unearthed from local larders and hear echoes of the jangle of bells announcing ovine movement several kilometers distant. However, what I know I will keep with me longer than any fleeting sensory memories of my trip is a deep and lasting appreciation for the incredible hospitality that I was shown by everyone I met on my visit to these timeless mountains.

There are a series of summits just outside of the city limits that are accessible off of main roads as you cross into one of the outer barrios of Jaén. However, after a certain point the paved roads dwindle to gravel roads, the gravel roads dwindle to dirt paths, the dirt paths dwindle to goat tracks, and occasionally the goat tracks dwindle to nothing. At such points, I focused on the few meters in front of me and kept climbing higher and higher, trying not to spend too much time looking down, because when I did I would see views like this:

There are a series of summits just outside of the city limits that are accessible off of main roads as you cross into one of the outer barrios of Jaén. However, after a certain point the paved roads dwindle to gravel roads, the gravel roads dwindle to dirt paths, the dirt paths dwindle to goat tracks, and occasionally the goat tracks dwindle to nothing. At such points, I focused on the few meters in front of me and kept climbing higher and higher, trying not to spend too much time looking down, because when I did I would see views like this: After summiting Los Morteros (the jagged dark gray ridge line visible in the first photo), I decided to return to the Castillo Santa Catalina via El Neveral, a gently domed peak that appeared to lead directly back to the fortress (appeared being the operative word here; a story for another time).

After summiting Los Morteros (the jagged dark gray ridge line visible in the first photo), I decided to return to the Castillo Santa Catalina via El Neveral, a gently domed peak that appeared to lead directly back to the fortress (appeared being the operative word here; a story for another time).

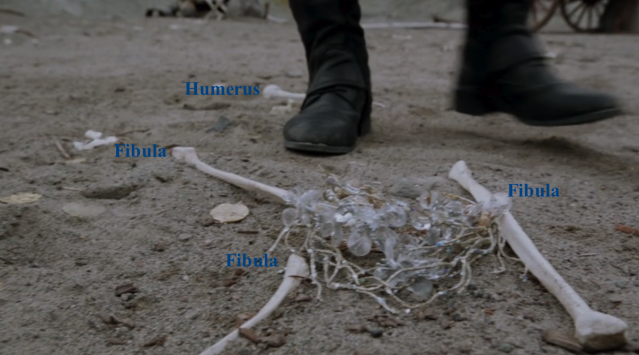

After the initial excitement wore off, I realized there might be more comparative specimens just lying around for the taking – possibly even a cranium. I explored the area for a few minutes, and while I didn’t find a cranium, I did spot a few other tell-tale splashes of white in the landscape, marked with arrows in the following photograph:

After the initial excitement wore off, I realized there might be more comparative specimens just lying around for the taking – possibly even a cranium. I explored the area for a few minutes, and while I didn’t find a cranium, I did spot a few other tell-tale splashes of white in the landscape, marked with arrows in the following photograph: I found the bones fairly close to the summit, and while I’m not a zooarchaeologist, there’s a few things I was able to tell right off of the bat. My questions for you, intrepid and equal-opportunity osteologists, are as follows:

I found the bones fairly close to the summit, and while I’m not a zooarchaeologist, there’s a few things I was able to tell right off of the bat. My questions for you, intrepid and equal-opportunity osteologists, are as follows:

While just a few hours later, we see her at the prince’s side, elbows extended. No evidence of discomfort whatsoever.

While just a few hours later, we see her at the prince’s side, elbows extended. No evidence of discomfort whatsoever.