I recently found a short synopsis I’d written a few years back about the etiology of cribra orbitalia and porotic hyperostosis. I think that this was initially meant to go into my predoctoral paper, before I realized that I did not want my predoctoral paper to be 3oo pages long. Despite its lack of utility for that requirement , it’s still a useful introduction to both pathologies. In the interest of not condemning this short literature review to a life of languishing on a folder on my desktop, I’m publishing it here for the time being.

Happy weekend everybody!

Porotic Hyperostosis and Cribra Orbitalia: A brief literature review

Porotic hyperostosis presents as macroscopic porosity on the flat bones of the cranium, particularly the frontal, parietal and occipital bones (Stuart-Macadam 1987), producing a characteristically “coral-like” or “sieve-like appearance” on the compact bone of the cranium (Goodman & Martin 2002; Walper et al. 2007).

Porotic hyperostosis on a parietal

Cribra orbitalia is similar in appearance to porotic hyperostosis, but occurs only on the orbital roofs. Many researchers treat cribra orbitalia as a symptom that results from the same etiological and pathological processes as porotic hyperostosis (Angell 1966; Stuart-Macadam 1985, 1987, 1992) though more recent research challenges this assumption (Walker et al., 2009).

Cribra orbitalia

Extensive radiographic and histological studies have demonstrated that porotic hyperostosis is brought about by an expansion of the hematopoietic diploë at the expense of a rapidly thinning outer table (Stuart-Macadam 1987). Marrow hypertrophy is instigated by lowered levels of hemoglobin in the blood, resulting from either a decrease in the number of red blood cells or a decrease in the levels of hemoglobin available within red blood cells. Early research on the frequency of hyperostosis in prehistoric Old World populations emphasized the adaptive resistance to malaria conferred by heterozygosity for thalessemia and sickle cell anemia (Angel 1966), but this etiology was inappropriate for New World populations that also demonstrated high frequencies of porotic hyperostosis. Accordingly, iron deficiency anemia gained increasing popularity as the primary agent responsible for the development of such lesions (Holland et al., 1997; Roberts & Manchester 2005).

It has long been acknowledged that the frequency of porotic hyperostosis increases regionally with the adoption of agriculture (Cohen & Armelagos 1984), and the ‘maize-dependency’ hypothesis suggests that a reliance on cereal grains, which are low in iron, as staple foods, led to the fluorescence of porotic hyperostosis that appeared subsequent to the increasing reliance on domesticated crops around the world. In addition to being poor sources of iron themselves, cereal grains like maize contain phytic acid, which has a deleterious effect on the ability of the intestine to absorb dietary iron (Holland & O’Brien 1997).

It’s a-maizeing how much this impedes iron absorption! (See what I did there).

Importantly, however, iron deficiency anemia does not always result from nutritional deficiencies, but can be brought about by blood loss, pregnancy, growth processes, menstruation, chronic disease, poor hygiene, vitamin C deficiency, gastrointestinal ulcers, and parasitic infection (Stuart-Macadam 1992; Wapler et al. 2004; Roberts & Manchester 2005). Some causal explanations for porotic hyperostosis go so far as to underscore its potentially adaptive status – because pathogenic micro-organisms rely on their hosts to supply them with iron, Stuart-Macadam (1992) has argued that a chronic hypoferremic (or iron-deficient) state is an evolved physiological response to high pathogen loads, rather than a symptom of iron deficiency anemia brought about by nutritional deficiencies. She notes that archaeologically observed cases of porotic hyperostosis increase in frequency the closer the parent population to the equator, a distribution which likely mirrors that of micro-organisms which thrive in hot and humid climates. However, other researchers have underscored that this distribution overlaps significantly with early agricultural centers, and that prime mover explanations are overly simplistic, noting that it is likely that “nothing is the major factor; rather there may be (and most likely is) a multitude of more-or-less equally important, and interdependent factors” (Holland & O’Brien 1997:191) that contribute to the etiology of the disease.

Iron. This kind likely wouldn’t help you with porotic hyperostosis, though.

Recent research on porotic hyperostosis, however, has challenged the explanatory efficacy of both the pathogen-load model and the iron deficiency model. While many archaeologists have portrayed the physiological response to anemia as a fairly simple process, in which a severe reduction in hemoglobin or hematocrit levels triggers marrow hypertrophy, Walker et al. (2009) underscore that the body’s response to anemic insult is more complex, involving a hierarchical series of reactions. When the body becomes hypoxic it releases the hormone erythropoietin, which stimulates the accelerated production and maturation of red blood cells. It is only after this initial hormonal response fails that bone marrow is called into action to produce more red blood cells. Because the process of erythropoiesis is responsible for the marrow hypertrophy which defines porotic hyperostosis, and because erythropoiesis requires sufficient iron stores, “the simple fact that iron-deficiency anemia effectively decreases mature red blood cell production means that it cannot possibly be responsible for the osseous expression of hemopoietic marrow expansion that paleopathologists recognize as porotic hyperostosis and cribra orbitalia”(Walker et al. 2009: 112). Instead, hemolytic anemias like thalassemia or sickle cell anemia (which occur when red blood cells are destroyed prematurely) or megaloblastic anemias (which result from dietary deficiencies and malabsorption of folic acids and vitamin B12) are more convincing etiological culprits. The prevalence of porotic hyperostosis in the Old World can thus be most profitably explained with reference to the hemolytic anemias, particularly in light of their anti-malarial effects. In the New World, however, porotic hyperostosis was likely symptomatic of the megaloblastic anemias, rooted in “the synergestic effects of nutritionally inadequate diets, poor sanitation, infectious disease, and cultural practices related to pregnancy and breast-feeding”(Walker et al. 2009: 114) that combined to limit individuals’ access to foods of animal origin.

Gross.

Finally, recent research has also begun to more carefully interrogate the relationship between porotic hyperostosis and cribra orbitalia. Past studies which combined radiographic, clinical and demographic data have suggested that both pathologies share the same etiology (Stuart-Macadam 1987), but in a recent study of a Nubian sample, in which a thin-ground sections were sampled from 85 individuals evincing cribra orbitalia, only 35.3% of the cases identified macroscopically demonstrated the histological features characteristic of anemia (Wapler et al. 2004). The apocryphal diagnoses resulted from postmortem erosion, hypervascularisation and osteitis, among other factors. Similarly, insults other than anemia, particularly scurvy, rickets, hemangiomas and traumatic lesions can produce subperiosteal inflammation or hematomas. Walker et al. report that “during the healing processes, these blood clots are transformed into plaques of highly vascular, superiosteal new bone that on gross examination can appear identical to cribra orbitalia”(115).

While the etiologies of porotic hyperostosis and cribra orbitalia are fiercely debated in the literature, there is strong agreement about their connection to human life histories. In nearly every study conducted, porotic hyperostosis is found to overwhelmingly affect children and juveniles in terms of both its frequency and potency of expression (Stuart-Macadam 1985; Holland & O’Brien 1997). Many processes that exacerbate or foster conditions of both chronic iron deficiency anemia and megaloblastic anemia, such as long periods of breast-feeding, weaning onto low iron cereal staples, and diarrheal disease, differentially affect young children (Holland & O’Brien 1997; Walker et al. 2009).

Physiologically, this tendency is underscored by differences between the functional import of bone in children and adults. Because children devote the majority of their marrow space to hematogenesis, there is limited additional room for marrow hypertrophy, and so the diploë begins to expand at the expense of the outer table. In contrast, a far higher proportion of bone marrow in adults is yellow marrow, devoted to storing fat rather than producing red blood cells. In times of hypoxic strife, adults can convert inactive yellow marrow into red marrow, an option unavailable to younger individuals. Similarly, because young children have more malleable and plastic bones, the pressure wrought by the ‘overcrowded’ hypertrophic marrow creates far more extreme alterations in the outer table than would be possible in the firmer cortex of an adult (Stuart-Macadam 1985). Cribra orbitalia is similar in its differential impact on younger individuals, whether the presumed etiology is iron deficiency anemia (Stuart-Macadam 1985), pathogen-load (Stuart-Macadam 1992), or subperiosteal bleeding (Walker et al., 2009). Because (i) the periosteum of children is more loosely attached to the orbital roof, and (ii) children have a higher density of blood vessels connecting the periosteum to the orbital roof, “orbital roof hematomas most commonly occur in children (Walker et al. 2009: 116).

Accordingly, there is general agreement that these pathologies are indicative of insults suffered during childhood, rather than adulthood. While multiple etiologies have been proposed for both conditions, including iron-deficiency anemia (Holland & O’Brien 1997), pathogen resistance (Stuart-Macadam 1992), hemolytic anemias (Angel 1966), megaloblastic anemias (Walker et al. 2009), or other infections or dietary deficiencies (Wapler et al. 2004; Walker et al. 2009), many are exacerbated by similar environmental conditions. In particular, the mutually reinforcing effects of a decreased reliance on animal foods, increased sedentism and crowding, unhygienic living conditions, longer periods of breastfeeding, and increasing levels of diarrheal disease are likely to have instigated increased levels of porotic hyperostosis and cribra orbitalia in prehistory, no matter what the proximate cause of the pathology.

References

Angel, J. (1966). Porotic Hyperostosis, Anemias, Malarias, and Marshes in the Prehistoric Eastern Mediterranean Science, 153 (3737), 760-763 DOI: 10.1126/science.153.3737.760

Angel, J. (1966). Porotic Hyperostosis, Anemias, Malarias, and Marshes in the Prehistoric Eastern Mediterranean Science, 153 (3737), 760-763 DOI: 10.1126/science.153.3737.760

Holland, T., & O’Brien, M. (1997). Parasites, Porotic Hyperostosis, and the Implications of Changing Perspectives American Antiquity, 62 (2) DOI: 10.2307/282505

Holland, T., & O’Brien, M. (1997). Parasites, Porotic Hyperostosis, and the Implications of Changing Perspectives American Antiquity, 62 (2) DOI: 10.2307/282505

Stuart-Macadam, P. (1985). Porotic hyperostosis: Representative of a childhood condition American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 66 (4), 391-398 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.1330660407

Stuart-Macadam, P. (1985). Porotic hyperostosis: Representative of a childhood condition American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 66 (4), 391-398 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.1330660407

Stuart-Macadam, P. (1987). Porotic hyperostosis: New evidence to support the anemia theory American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 74 (4), 521-526 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.1330740410

Stuart-Macadam, P. (1987). Porotic hyperostosis: New evidence to support the anemia theory American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 74 (4), 521-526 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.1330740410

Stuart-Macadam, P. (1992). Porotic hyperostosis: A new perspective American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 87 (1), 39-47 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.1330870105

Stuart-Macadam, P. (1992). Porotic hyperostosis: A new perspective American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 87 (1), 39-47 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.1330870105

Roberts, Charlotte and Keith Manchester. 2005. The Archaeology of Disease. Third Edition. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Roberts, Charlotte and Keith Manchester. 2005. The Archaeology of Disease. Third Edition. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Walker, P., Bathurst, R., Richman, R., Gjerdrum, T., & Andrushko, V. (2009). The causes of porotic hyperostosis and cribra orbitalia: A reappraisal of the iron-deficiency-anemia hypothesis American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 139 (2), 109-125 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.21031

Walker, P., Bathurst, R., Richman, R., Gjerdrum, T., & Andrushko, V. (2009). The causes of porotic hyperostosis and cribra orbitalia: A reappraisal of the iron-deficiency-anemia hypothesis American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 139 (2), 109-125 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.21031

Wapler, U., Crubézy, E., & Schultz, M. (2004). Is cribra orbitalia synonymous with anemia? Analysis and interpretation of cranial pathology in Sudan American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 123 (4), 333-339 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.10321

Wapler, U., Crubézy, E., & Schultz, M. (2004). Is cribra orbitalia synonymous with anemia? Analysis and interpretation of cranial pathology in Sudan American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 123 (4), 333-339 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.10321

Image Credits: Porotic hyperostosis on parietal from University of Florida page, here. Cribra orbitalia on orbits found here. Malarial vector found here.Image of anvil found here. Bone marrow diagram found on dxline website.

At the AAPAs, the

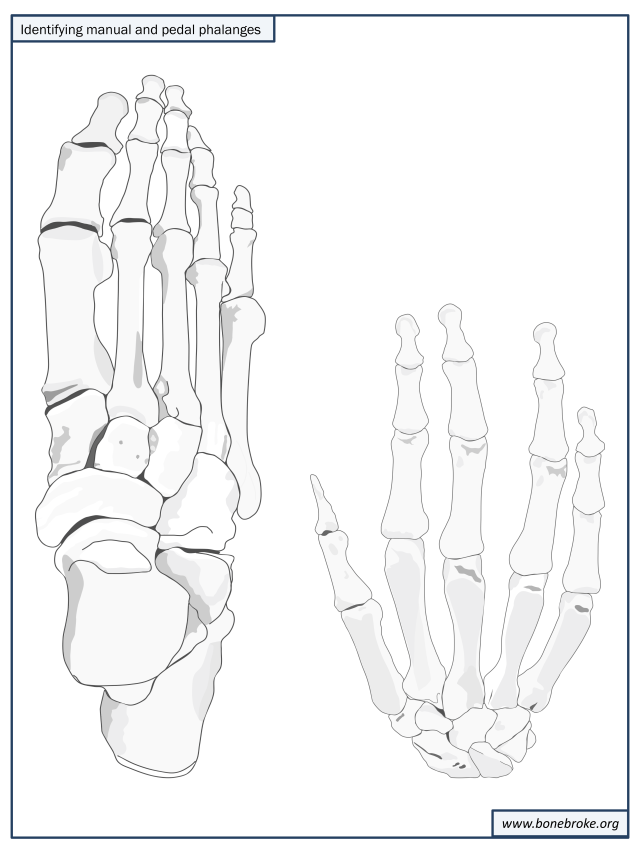

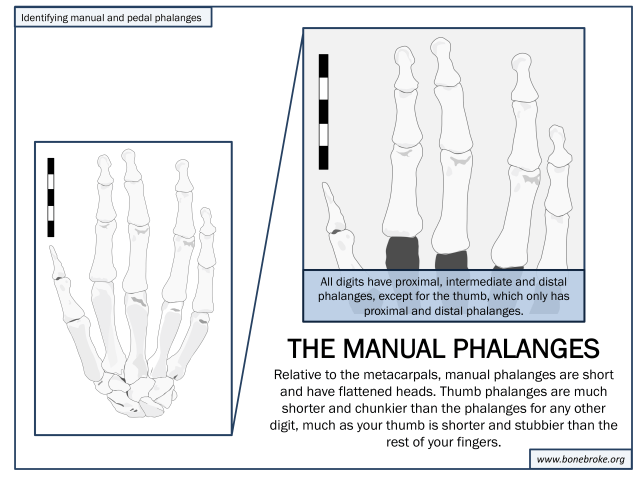

At the AAPAs, the  You can use essentially the same rules of thumb (and why yes, my wit has grown even more incisive since arriving in a city where almost no one speaks English, thank you for noticing) for distinguishing the pedal phalanges from the metatarsals:

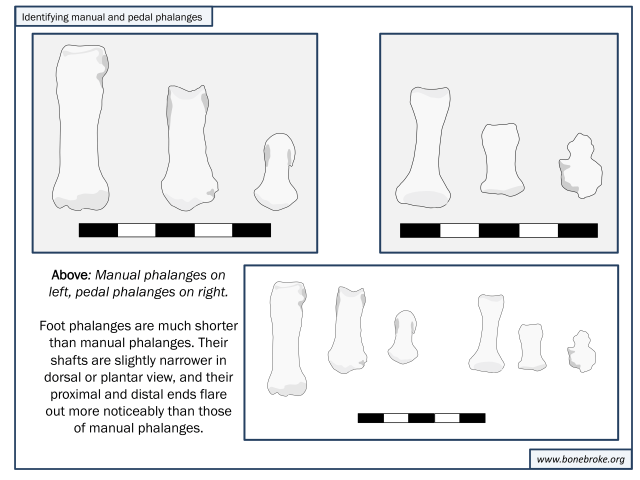

You can use essentially the same rules of thumb (and why yes, my wit has grown even more incisive since arriving in a city where almost no one speaks English, thank you for noticing) for distinguishing the pedal phalanges from the metatarsals: 2. Is it a manual phalanx or a pedal phalanx?

2. Is it a manual phalanx or a pedal phalanx? The shape of the shaft in cross-section is also diagnostic, since the shafts of pedal phalanges are circular, while those of manual phalanges form half-moons. Finally the presence or absence of rugose muscle-attachment sites is also telling, since such markings characterize manual phalanges rather than pedal phalanges.

The shape of the shaft in cross-section is also diagnostic, since the shafts of pedal phalanges are circular, while those of manual phalanges form half-moons. Finally the presence or absence of rugose muscle-attachment sites is also telling, since such markings characterize manual phalanges rather than pedal phalanges.